Article

1Pedagogical University of Cracow, Poland.

2Pedagogical University of Cracow, Poland.

Problematic Internet use (PIU) is one of the most notable of all Internet threats. Young people are one of the groups at particular risk of PIU. PIU has become a research and educational priority due to its scale and the accompanying shifts in the media pedagogy paradigm. PIU is also the subject of many discussions and raises many methodological questions. The goal of the present study was to highlight the scale of PIU, and its accompanying protective factors related to interests, emotions and offline time spent on developing hobbies and passions. The study was conducted in 2016 in Poland, among 663 school students aged 17.93 (SD = 1.46), by means of triangulation of quantitative research methods. The scale of PIU was determined using a shortened version of Young’s Internet Addiction test. Warning symptoms of PIU were found in 23.52% of the respondents (“yellow light”), whereas full PIU can be observed in 5.88% of the students (the results are independent of gender). Thus, the stereotypical view that PIU is common is not true. PIU is connected with negative emotions offline (mostly boredom and a lack of self-control) and too little time spent on developing passions and interests. PIU presents a challenge in terms of both research and prevention. Depending on the criteria adopted, the scale of young people at risk of PIU changes. PIU is connected with offline activities. Failure to provide effective media education (focused on strengthening self-control when using new media) and neglecting individual passions and interests intensify PIU. Further discussion of the key factors that would allow PIU to be more clearly determined is also necessary.

Keywords: youths • Internet addiction • family • problematic Internet use • free time •Poland

Received: 23 April 2019; Revision Received: 3 July 2019; Accepted: 9 July 2019

Author for correspondence: ŁukaszTomczyk, PhD, Faculty of Pedagogy, Pedagogical University of Cracow. Ul. Ingardena 4, 30-060 Krakow, Poland. E-mail address: Tomczyk_lukasz@prokonto.pl

How to cite: Tomczyk, L., &Solecki, R. (2019).Problematic internet use and protective factors related to family and free time activities among young people. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 19(3),1 - 13. http://dx.doi.org/10.12738/estp.2019.3.001

Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12738/estp.2019.3.001

Copyright: Tomczyk, L., &Solecki, R.

License: This open access article is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

The present research of the use of media in education takes two forms.The first assumes the constructive use of the Internet, phones and different types of computers. In this perspective, digital media and the Internet are a source of information and stimulate development, so in general, they affect human development and functioning in a positive way (Pyżalski, 2017). This opportunity paradigm was one of the first recognised and developed in media pedagogy. At the other end of the spectrum of human-media relations is the risk paradigm (Pyżalski, 2016) which assumes that the Internet, phones, and computers cause destructive changes in the physical and mental spheres. The paradigms clash, most notably in their differentinterpretations of the same phenomena, for example the problematic Internet use presented herein. The research presented has been intentionally rooted in the risk paradigm, yet with a note that we will emphasisethe negative consequences of Internet overuse though without creating stereotypes (which does appear tohappen in selected scientific publications reviewed in Poland).

Behavioural addiction (addictive behaviours) are compulsive behaviours - performed under an unmanageable, inner urge - that bring about the release of emotional tension caused byproblems in life, together with relief and psychical pleasure (Young, 2009).This group of addictions includes thepathological use of media, especially, the Internet. This is a relatively new form of behavioural addictionassociated with risky behaviours in the area of cyberspace, television and mobile phones. As a result ofrelationships now being mediated by different technologies, the population affected by compulsive mediause is growing (Macuch et al., 2018; NovkovićCvetković, Stošić, & Belousova, 2018;Ogonowska, 2014).

When speaking about media addiction, this study finds terms like phono holism, net addiction,cyber addictions, cyberholism (Arlsan et al., 2015;Jędrzejko, 2013;Kopecký, Szotkowski, &Krejčí, 2015; Potyrała, 2017). Obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance-related addiction and abuse are listed in the DSM (a classification of mental disorders created by the American Psychiatric Association). Internet addiction is compared to substance addiction through reference to the so-called withdrawal syndrome and increased tolerance (Aboujaoude, 2012; Bányai et al., 2017). It has been known for over a dozen years that technology “addictions” share some common characteristics and that the consequences of using technology are of an economical, health, and psychosocial nature. However, these forms of addiction are not yet listed in the international classifications of diseases (ICD-10, DSM V) because they are considered to be disorders (addictions) rather than diseases (Jędrzejko, 2013; Király et al., 2014). There is no single approach to this phenomenon among researchers, so we find such terms as: Internet addiction, proposed byYoung andClausing (2009), pathological Internet use suggested by Davis (2001), the compulsive use of new media or cyber disorders byJędrzejko (2013)orRębisz, Sikora, and Smoleń-Rębisz(2016).

Advocates of the diagnosis of Internet addiction also compare it with impulse control disorders. One common characteristic of these disorders is the unstoppable desire to implement behaviour, which is very satisfying at the given moment, but from a longer perspective leads to feelings of guilt and suffering(Aboujaoude, 2012).

Due to the difficulties in strictly defining the phenomenon, the concept of problematic Internet use given by Davis was adopted for this study. Davis (2009) identified two types of Internet-related disorders: (i) Aspecific pathological Internet use (SPIU) - that refers to using the Internet in a way that aggravates an already existing addiction (gambling, shopping, pornography). It is dependent on certain functions of the Internet, connected with only one of itsaspects, and it exists independently of its various functions. Thus, the negative consequences in this groupare secondary. (ii) A generalised pathological Internet use (GPIU)- this refers to the general opportunities provided by the Internet, like surfing the web, chatting etc. People with thisInternet-related disorder often spend many hours online without a specific goal. It is multidimensional overuse, connected with the social aspect of the Internet and its many possibilities which often become a substitute for the real world.

In Poland, Poprawa (2013), among others, suggested that the PIU phenomenon is present among 2% of respondents aged 15-19, whereas 13% are at risk of PIU. The EU NET ADB study (Makaruk&Wójcik, 2012) also showed that in Poland, like in other European countries, only a small percentage (1.3% of respondents) meet the criteria for Internet overuse. The majority group are individuals with only some symptoms, thus presently at risk of overuse (among 12.1% of Polish teenagers).According to a 2016 report byNaczelna Izba Kontroli [Supreme Audit Office] (NIK), it is estimated that between 18% and 38% of Polish teenagers noted that they had symptoms of Internet addiction. The data change depending on the methodological perspective adopted or the indicators used in the research tool (NIK, 2016). It is worth adding that about 30% of Polish teenagers are online all the time and everywhere. Polish researchers emphasise that the number of young Internet users, who use new technologies in destructive ways, is on the increase. The phenomenon has been noticed not only by parents and teachers, but also by the youngest generations of e-service users (Mróz&Solecki, 2017; Tomczyk&Selmanagic-Lizde, 2018; Tomczyk&Wąsiński, 2017).

When analysing the different methodological approaches outside of Poland it has been noted thatabout 12% of teenagers in Japan show symptoms of PIU– according to a representative study in youngpeople (Morioka et al., 2016). Depending on the methods adopted, the diagnostic tools used and the PIUindicators selected, the phenomenon sitsaround 12%. For example, Indian research indicates that more than 16% of young people have full-symptomatic PIU (Vadheret al., 2019). A similar percentage of individuals at risk of PIU has been noticed by Hungarian researchers who studied risky behaviours among adolescents (Demetrovics et al., 2016). Researchers from Denmark also haveobtained results of around 11%ofadolescents engaged in PIU (Jelenchick, Hawk, & Moreno, 2016).

The analyses of PIU have revealed many interesting correlations with other risk factors. One of the findings was that PIU is associated with peer aggression and withdrawal from the peer group, which means it is rooted in social relationships (Zhai et al., 2019). The above-mentioned results are similar to the correlations observed in other countries. For example, Greek researchers have noticed that PIU coexists with being a victim of cyberbullying or with the sense of loneliness and disagreeableness (Kokkinos & Antoniadou, 2019). According to Portuguese scientists, loneliness coexists with PIU regardless of age (Costa,Patrão, & Machado, 2019). Researchers highlight the importance of relationships in the individual’s primary and secondary environment. For individuals in their early adolescence, the relationships with parents had the greatest influence on the level of Social Network Sites (SNS) addiction which is part of PIU. In late adolescence, peer relationships become more important. Both factors affect PIU level with different strength, being at the same time protective factors (Badenes-Ribera, Fabris, Gastaldi, Prino, &Longobardi, 2019). Psychologists also point out the role of personality in the development of PIU. PIU is largely shaped by low agreeableness, low conscientiousness, high openness and high neuroticism (Xiao et al., 2019). Of course, the investigators of gaming and gambling emphasise the importance of duration and the time of the day spent on these types of activities (Andrie et al., 2019). PIU is often associated with a high percentage of risky online behaviours like sexting (Gansner et al., 2019). Like Internet addiction, PIU is also considered in the context of many disorders which result from sleep problems for instance (Guo et al., 2018).

The Internet behaviour dependence(IBD) concept introduced by Hall and Parsons (2001)indicates that network usage-related problems result from the mechanism of compensation for the deficits individuals experience in other areas of their functioning. The theory of usage and gratification also includes the thesis that individuals use media to meet certain needs. In this context, McQuail (1984) talks about the benefits that accrue from using new media, such as information, identity, social integration and interaction, and entertainment. The EU NET ADB report showed that all the people who make dysfunctional use of the Internet, evaluated all aspects of their life lower than functional Internet users.Low life satisfaction may be connected with many other problems.Therefore, this relationship should be further analysed in the context of Internet overuse (Makaruk&Wójcik, 2012). This has been confirmed by studiesof Poprawa (2012), conducted among adolescents, which suggested that there was a correlation between the expected results of using the Internet and its pathological use. The strongest predictor was compensatory expectations related with building close relationships, looking for acceptance and a sense of self-worth, and escaping problems, as well as searching for a space to express suppressed emotions (Oleszkowicz&Senejko, 2013). The relationship between problematic use of the Internet and compensatory and hedonistic expectations are the strongest in the group of 11-16-year-olds, that is, early adolescents. At the same time, compared to others, this group shows the highest level of compensatory expectations (n = 4007, 11-65 years) (Poprawa, 2009; 2012).

Therefore, we decided to analyse the emotions that accompany online activities, hobbies, time spent on developing online relationships, and the intensity of online activities (using e-services).The objective of the study was to delineate the specifics of PIU among late adolescents. The main objective was connected with two specific objectives: the diagnosis of the scale of PIU, and the identification of protective and risk factors accompanying PIU and rooted in leisure activities, emotions experienced in online and offline spaces, and the means by which new media are used. The research objective was determined by the risk paradigm of media pedagogy, exemplified by the results of a variety of studies, for example NIK (2016), DzieciSieci (Siuda et al., 2013), Nastolatki 3.0 (NaukowaiAkademickaSiećKomputerowa[Scientific and Academic Computer Network - NASK], 2016), CyfrowoBezpieczni(Tomczyk, Srokowski, &Wąsiński, 2016), all of which emphasise the scale of PIU risk among young Internet users. Asmentioned above the risk paradigm is one of the methodological perspectives in Polish media pedagogy.The analysis of risky behaviours among young people, focused on e-threats, serves to explore the full rangeof determinants of a given phenomenon, PIU in this case. The identification of risk factors allows us notonly to understand the phenomenon, but also to design activities which would help to prevent it.

The study was conducted in the Małopolska region (Lesser Poland), in the school year 2016/2017, among 663 upper-secondary school students. The sample consisted of 353 girls (53.24%) and 310 boys (46.76%). The average age was 17.93, with SD=1.46. The respondents lived in: a village (n =351, 52.94%), a large city (n =119, 17.95%), and other types of city/town (n=193, 29.11%). As for family environment, 97.72% lived with their mother (n =643), compared with 87.10% with their father (n=567). The total number of students in the school year was 127,000. The schools that participated in the study were selected randomly.Using the Educational Information Centre system, we can state that our sample enables a generalisation of results at confidence level α = .98, with maximum error not exceeding 5%.

A battery of tests was used to determine the correlations between PIU and the attendant protective factors and factors accelerating problematic Internet use. The battery of tests was developed for the purposes of this study. The variables and parameters were selected based on areas typical for family and media pedagogy. The whole tool is highly internally consistent at a level of .85.The final version of the tool included the following tests measuring:

A scale of typical online activities consisting of 25 items, including gambling, shopping and auctions, mail, online gaming – single player, looking at photos posted by friends, reading blogs, reading information, FPS online games, communicators, watching movies, looking at erotic videos and photos, listening to music, doing homework, RPG, participating in forums, learning, reading articles, developing a hobby, software downloads, commenting on posts, video downloads, chatting, RTS, searching for information, writing their own blog. The frequency of use for the different services was presented on an 8-level scale (0 = never, 7 = seven times a week). The internal consistency for this extended module was .78.

A scale of most frequent negative emotions felt during online activities, including 9 items: anxiety, fear, excitement, anger, frustration, envy, guilt, helplessness, and sadness. The internal consistency for this scale was .84.

Declarations of positive emotions felt during online activities. The tool consisted of 7 items covering such factors determining Internet use as: desire to develop one’s interests, staying in contact with friends, curiosity about the activities of others, looking for new experiences, the desire to be up-to-date, the desire to improve one’s mood, and looking for new friends. Answers to the question about negative emotions were given on a standard Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The Cronbach alfa for this scale was .77.

Declarations of negative emotions accompanying activities connected with new technologies, which included 5 items: boredom, sadness, internal urge, escaping problems, and loneliness. Answers to the question about negative emotions were given on a standard Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The Cronbach alfa for this scale was .75.

A scale of engaging in activities other than using the Internet. The test consists of 8 items that measure engagement in conversations with other family members and friends, offline meetings, studying, sports, watching TV, and pursuing passions. Every variable was a numeric result (estimated time spent daily on these activities, in minutes). The internal consistency for this scale was .73.

A scale of developing personal passions and interests in the institutional context. This module asked how often respondents take part in activities that facilitate the development of their hobbies and their predispositions (talents). This test consists of 6 items identifying certain institutions and informal groups in the local environment (school, home, cultural centre, sport training, peer group, art group), where young people develop their passions. The whole tool was highly internally consistent at .77.

Internet Addiction Scale(abbreviated version)by Young (2016). This is a scale measuring 3 levels of network use. The abbreviated version consisted of 8 questions with nominal answers. One point was given for each answer indicating PIU. The results were then summed up, where 0 = no PIU symptoms to8 = full set of PIU symptoms.

Additionally, the tool included questions about the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample: gender, year of birth, place of residence, family structure, number of siblings, and parents’ educational background. The questionnaire also had questions about following rules, average grades obtained in the previous semester, and the number of hours spent on the Internet.

The research was conducted in accordance with ethical principles. The adolescents answered the questionnaires voluntarily and they were informed about the scientific goal of the study and the data processing procedure. The questionnaires were distributed among minors upon their consent and the consent of school directors and teachers. The ethics process required two-stage consent (school directors and teachers, then the adolescents themselves). The survey was conducted in schools which provide compulsory education. The interviewers presented the objectives of the research and informed the respondents that the survey was completely anonymous. Due to the nature of the sample (many individuals had achieved their majority already and were no longer minors), we did not ask for their parents’ consent. The research process was supervised by the team who designed the questionnaire (researchers with experience in social research in representative samples).

The analysis was made using the distribution of variables.Table 2 presents the cumulativeoccurrence of PIU factors. The authors are aware that the presence of one factor at its maximum strength does not prove a fully symptomatic PIU. Therefore, we recommend presenting PIU in a multidimensional perspective, that is, showing the cumulative PIU predictors. This has been done in other international research in this area, for example EUKIDS Online (Pyżalski, Zdrodowska, Tomczyk, &Abramczuk, 2019).The relationships between other nominal and numeric variables were determined by means of a single-factor variance analysis, whereas the co-existence of the numeric indicators (Likert scale) was illustrated using Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient. Given the model developed connected with free time and PIU, a multilinear regression model was designed using STATISTICA 12 which enabled the holistic presentation of changes in the intensity of certain traits in the case of more intense PIU.

The most noticeable PIU symptoms include a lack of self-control regarding the time spent online. More than half of the respondents declared having struggled in this area. The two others most common PIU predictors are the desire to escape problems and improving one’s mood. One in five young new media users tried to limit the time they spent using ICT but failed. Table 1 presents the percentage distribution of answers to the abbreviated version of Young’s test.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of factors characterising problematic Internet use(%)

% |

N = 663 |

|

I constantly think about the Internet |

18.52 |

123 |

I use Internet more and more often to find pleasure |

17.77 |

118 |

I tried to cut down the amount of time spent online but failed |

21.54 |

143 |

I felt anxiety and other negative emotions when I tried to limit using Internet |

16.27 |

108 |

I stay online longer than I intended |

57.53 |

381 |

I risk losing close relationships because I use Internet |

8.73 |

58 |

I lied to my loved ones or other people to hide my problem with PIU |

11.90 |

79 |

I use Internet to run from my problems or improve my mood. |

31.17 |

207 |

Considering the three styles of using the Internet (functional, with some PIU symptoms, andfully symptomatic PIU), 70.58% of the respondents were ata constructive and functional level with minimum or non-existing symptoms of PIU. Level II, that is, individuals showing 3-5 symptoms from theInternet Addiction (IAD) test, constitute 23.52% of the group. Full PIU or the “red light” group account for 5.88% of the respondents. The percentage and cumulative distribution of the answers is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Cumulative number and item number of problematic Internet use factors

Factors — cumulative number |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

182 |

182 |

27.45 |

27.45 |

||||

|

171 |

353 |

25.79 |

53.24 |

||||

|

115 |

468 |

17.34 |

70.58 |

||||

|

82 |

550 |

12.36 |

82.95 |

||||

|

51 |

601 |

7.69 |

90.64 |

||||

|

23 |

624 |

3.46 |

94.11 |

||||

|

28 |

652 |

4.22 |

98.34 |

||||

|

4 |

656 |

0.60 |

98.94 |

||||

|

7 |

663 |

1.05 |

100.00 |

In the sample group, PIU is more frequent among boys than girls F (1, 662) = 15.71, p< .00. The place of residence does not determine problems with using the Internet in a statistically noticeable way F(2, 661) = .67, p > .05. Having one parent or no parents does not determine PIU in a statistically relevant way, and nor does living with siblings or grandparents. The educational background of the father F(4, 629) = 1.68, p> .05 and mother F(3, 644) = .77, p > .05is not connected with the IAD test results. Young respondents who declared that they do not follow rules at school F(2, 658) = 8.85, p< .00, at home F(2, 658) = 5.05, p < .00, in their relationships with friends F(2, 656) = 6.09, p< .00 or in society F(2, 655) = 5.15, p < .00, show PIU symptoms more often.

There is a relationship between PIU and protective factors and factors increasing the risk of being in this group. Individuals who are more active Internet users, more often show signs of PIU. PIU is also significantly correlated with experiencing Negative emotions while being online, as well as Negative emotions felt offline (such as sadness, loneliness and others). The relationship between PIU and Negative emotions experienced offline is one of the strongest correlations revealed by the data analysis. The coexistence of Negative emotions experienced online and offline is another very visible correlation. Having an Offline hobby does not reduce the risk of PIU significantly. However, the longer the time spent on developing passions in the offline space, the smaller the risk of PIU.

Table 3. Linear correlation between problematic Internet use and interdependent variables

1. Internet activity scale |

2. Negative when online |

3. Positive emotions |

4. Negative emotions offline |

5. Offline hobby |

6. Offline passions time |

7. IAT K. Young |

||

|

.25*** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.41*** |

.37*** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.22*** |

.53*** |

.41*** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

.22*** |

.19*** |

.36*** |

.14*** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

.11** |

-.03 |

-.01 |

-.03 |

.10** |

1.00 |

|

|

|

.22*** |

.37*** |

.31*** |

.54*** |

.08* |

-.11** |

1.00 |

Note: *p < .01; ** p< .05; *** p < .001

Age was not related to PIU (r = .02), and nor were the number of siblings (r = .09), the number of friends in SNS (r = .09) or the average of school grades (r = .04). However, it is worth noticing that the more time spent weekly (r = .12,p< .05) or during the weekends (r = .15, p < .05) on using the Internet, the greater the risk of PIU.

Considering all the variables (tests used thanks to the triangulation of the research tools), and using multilinear regression analysis, a model was developed. The model is verifiable at 32%. The model adopted was based on the previous analyses by media educators who associate PIU with the self-control of emotions and behaviours (Błachnio&Przepiorka, 2015; Przepiórka&Błachnio, 2013) as well as the factors present in the closest socialising environment (Dębski, 2016). Despite high coefficient F and level of trust p, two variables cannot be classified as factors related to all the other variables and PIU. In the context of statistical relevance, Positive emotions and Having hobbies are not associated with PIU.

Table 4. Multilinear regression model — version 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

-1.41 |

0.33 |

-4.24 |

.00 |

||||||

|

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.18 |

0.06 |

2.68 |

.00 |

||||||

|

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.24 |

0.10 |

2.31 |

.02 |

||||||

|

0.06 |

0.03 |

0.14 |

0.09 |

1.54 |

.12 |

||||||

|

0.44 |

0.03 |

1.01 |

0.08 |

11.32 |

.00 |

||||||

|

-0.03 |

0.03 |

-0.09 |

0.10 |

-0.90 |

.36 |

||||||

|

-0.09 |

0.03 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-3.03 |

.00 |

||||||

R = .56; R2 = .32; F(6,656) = 52.51; p< .00 |

||||||||||||

For this reason, another model was developed, without the above-mentioned variables. This model shows a visible correlation between independent variables determining PIU and negative emotions in the offline sphere, high activity in various online environments, and negative feelings regarding the use of the Internet. It can be confirmed that the amount of time spent on offline activities (but not their number or type) is a protective factor against PIU.

Table 5. Multilinear regression model — version 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

-1.38 |

0.24 |

-5.68 |

.00 |

||||||

|

0.11 |

0.03 |

0.21 |

0.06 |

3.30 |

.00 |

||||||

|

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.26 |

0.10 |

2.48 |

.01 |

||||||

|

0.46 |

0.03 |

1.05 |

0.08 |

12.09 |

.00 |

||||||

4. Offline passions time |

-0.10 |

0.03 |

-0.00 |

0.00 |

-3.22 |

.00 |

||||||

R = .56; R2= .32; F (4.65) = 78.03; p< .00 |

||||||||||||

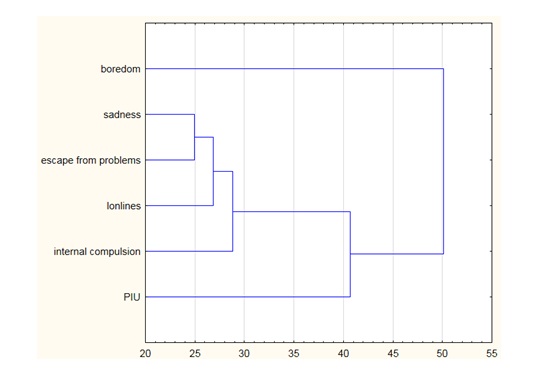

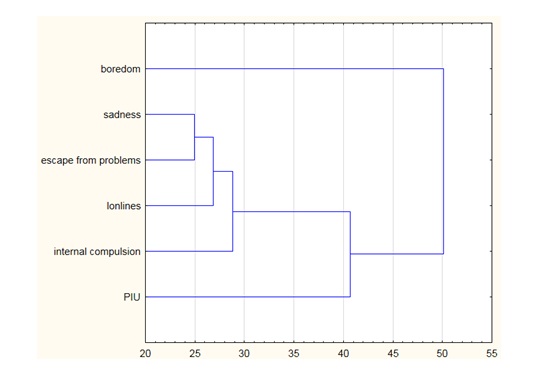

When using the cluster analysis method (see Figure 1) for the variable Negative emotions experienced offline, boredom is a dominating indicator. The indicator agglomeration technique showed that a lack of constructive activities is very strongly correlated with PIU. Internal urge and loneliness are next on the list but occur with less intensity.

Figure 1. Problematic Internet use cluster analysis

Thus, when discussing PIU, we should separate situational factors and those factors resulting from behaviour-related deficits (e.g., a lack of self-control).

Based on the results of the study it was found that the actual problem of pathological Internet use is smaller than is commonly believed in society. This analysis lays bare many stereotypes popularised by the media that a high percentage of today’s youth is addicted to new technologies (Błachnio&Przepiorka, 2016;Olszewska, 2013). PIU criteria are still not clear and therefore, the indicators adopted, and which depend on the research tools, change the perspectives of looking at the functional or destructive users of electronic media (Lai & Kwan, 2017;Pawłowska&Masiak, 2014). Problems with the definition of PIU are also valid for related addictions like gaming or online gambling (Plichta&Pyżalski, 2016). There is a noticeable discrepancy in analyses of PIU or, more widely, Internet addiction when we compare our study to previous Polish research (NASK, 2016;NIK, 2016). This is mainly due to the selection of different variables and scales for measuring PIU. The most challenging problems are to determine the scale of the phenomenon (presented differently in the context of the percentage share of people with PIU in the population) and to conduct longitudinal studies using clearly adopted criteria.

Given the results obtained, we have several interesting conclusions to make. Firstly, PIU is directly related to the ways in which new technologies are used. The duration of use, or the time of logging in, hasbeen become one of the more important PIU indicators (Demetrovics&Király, 2016;Przepiorka&Blachnio, 2016). However, it is worth not only measuring the time which may take different forms such as: only connecting to the Internet by enabling data transfer, screen time, and time spent on entertainment (new media as a substitute for old media). Instead, the time factor should be complemented with the emotional perspective of the young people, that is, how the negative and positive emotions related to the use of the Internet act as an indirect PIU variable. The researchers are aware that PIU is a multi-faceted phenomenon and many of its determinants are rooted in the closest environment, that is, the family (Pace et al., 2014; Pellerone, Ramaci, &Miccichè, 2019). Modelling the secure use of digital media is also connected with developing daily habits. The importance of this assumption has been proved by the data collected, which show that the lack of alternatives in the offline world (also those created by the closest family members) is one of the key factors accompanying prolonged, uncontrolled online activity. Alternatives like having a hobby or developing passions have become crucial factors that protect against PIU, IAD and fear of missing out (FOMO). For this reason, it is necessary to minimise these phenomena by developing attractive activities within the so-called anticipatory or primary prevention.

It is also worth emphasising that there is a constant need for a discussion of Internet threats among adolescents, because associating PIU with the addiction category creates a destructive psychosocial image of young people, thus strengthening the existing stereotypes or creating new ones (Davey et al., 2018). This study conducted within the risk paradigm of media pedagogy shows that problems with the definition and the scale of PIU should be analysed with much greater detail and with consideration to a range of factors connected with the style of media use (Bayraktar, 2017; Savci&Aysan, 2017), the specifics of the development of the information society, the individual characteristics of young people (Walotek-Ściańska, 2017; Ziemba, 2016) and offline activities. PIUis quite often connected with the problem of a lack of self-control (Jinha, Hyeongi, Jungeun, &Myoung-Ho, 2017). However, as revealed by our data, this factor is dominated by the factor of boredom which increases the general PIU score. A lack of alternative ways of spending free time is one of the situational factors which create problematic situations connected with using new media (Tomczyk&Wąsiński, 2017). Based on the data collected, we also noticed that another very important protective factor is the time spent on developing passions in the offline world not mediated by electronic media. Offline passions provide a successful alternative to boredom and, at the same time, they are a protective factor which strengthens self-control in the area of ICT use (Biolcati, Mancini, &Trombini, 2018).

PIU is a multidimensional phenomenon which is sometimes treated as a non-marginalising type of Internet addiction. In the subject matter literature, PIU is also treated as a phenomenon which, depending on environmental and individual factors, may evolve into Internet addiction. For this reason, further discussion of the diagnostic criteria is needed, as well as the improvement of related tools, for example those used in the context of FOMO, gaming, and gambling among young people (Fineberg et al., 2018;Spada, Caselli, Slaifer, Nikčević, &Sassaroli, 2014; Strittmatter et al., 2016).

Aboujaoude, E. (2012). Mroczna osobowość naszych czasów. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagilellońskiego.

Andrie, E. K., Tzavara, C. K., Tzavela, E., Richardson, C., Greydanus, D., Tsolia, M., & Tsitsika, A. K. (2019). Gambling involvement and problem gambling correlates among European adolescents: results from the European Network for Addictive Behaviour study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01706-w

Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Gastaldi, F. G. M., Prino, L. E., & Longobardi, C. (2019). Parent and peer attachment as predictors of Facebook addiction symptoms in different developmental stages (early adolescents and adolescents). Addictive Behaviours, 95, 226 - 232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.009

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M. D., … Demetrovics, Z. (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLOS ONE, 12, e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839

Bayraktar, F. (2017). Online risks and parental mediation strategies comparison of Turkish children/Adolescents who live in Turkey and Europe. Eğitim ve Bilim, 42, 25 - 37. https://doi.org/10.15390/eb.2017.6323

Biolcati, R., Mancini, G., & Trombini, E. (2018). Proneness to boredom and risk behaviours during adolescents’ free time. Psychological Reports, 121, 303 - 323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117724447

Błachnio, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2015). Dysfunction of self-regulation and self-control in Facebook addiction. Psychiatric Quarterly, 87, 493 - 500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9403-1

Błachnio, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2016). Personality and positive orientation in Internet and Facebook addiction. An empirical report from Poland. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 230 - 236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.018

Costa, R. M., Patrão, I., & Machado, M. (2019). Problematic internet use and feelings of loneliness. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 23, 160 - 162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2018.1539180

Davey, S., Davey, A., Raghav, S. K., Singh, J. V., Singh, N., Blachnio, A., & Przepiórka, A. (2018). Predictors and consequences of "Phubbing" among adolescents and youth in India: An impact evaluation study. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 25, 35 - 42. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_71_17

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioural model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 2, 187 - 195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8

Davis, R. A. (2009). Poznawczo-behawioralny model patologicznego używania Internetu. In J. Paluchowski (ed.), Internet a psychologia (pp. 373- 385). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Demetrovics, Z., & Király, O. (2016). Commentary on Baggio et al. (2016): Internet/gaming addiction is more than heavy use over time. Addiction, 111, 523 - 524. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13244

Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Koronczai, B., Griffiths, M. D., Nagygyörgy, K., Elekes, Z., … Urbán, R. (2016). Psychometric Properties of the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire Short-Form (PIUQ-SF-6) in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adolescents. PLoS ONE, 11, 1 - 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159409

Dębski, M. (2016). Nałogowe korzystanie z telefonów komórkowych. Gdańsk: Fundacja Dbam o Mój Zasieg.

Fineberg, N. A., Demetrovics, Z., Stein, D. J., Ioannidis, K., Potenza, M. N., Grünblatt, E., ... Grant, J. E. (2018). Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the Internet. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 1232 - 1246.

Gansner, M., Belfort, E., Cook, B., Leahy, C., Colon-Perez, A., Mirda, D., & Carson, N. (2019). Problematic Internet use and associated high-risk behaviour in an adolescent clinical sample: Results from a Survey of Psychiatrically Hospitalized Youth. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking, 22, 349 - 354. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0329

Guo, L., Luo, M., Wang, W.-X., Huang, G.-L., Xu, Y., Gao, X., … Zhang, W.-H. (2018). Association between problematic Internet use, sleep disturbance, and suicidal behaviour in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Behavioural Addictions, 7, 965 - 975. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.115

Hall, A. S., & Parsons, J. (2001). Internet addiction: College student case study using best practices in cognitive behaviour therapy. Journal of Mental Health Counselling, 4, 312 - 327.

Jelenchick, L. A., Hawk, S. T., & Moreno, M. A. (2016). Problematic internet use and social networking site use among Dutch adolescents. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 28, 119 - 121. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2014-0068

Jędrzejko, M. (2013). Uzależnienie czy zaburzenie? In M. Jędrzejko & D. Morańska (eds.), Pułapki współczesności. Cyfrowi tubylcy (pp. 251 – 284). Dąbrowa Górnicza-Warszawa: ASPRA-JR.

Jinha, K., Hyeongi, H., Jungeun, L., & Myoung-Ho, H. (2017). Effects of time perspective and self-control on procrastination and Internet addiction. Journal of Behavioural Addictions, 6, 229 - 236. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.017

Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., Urbán, R., Farkas, J., Kökönyei, G., Elekes, Z., … Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Problematic Internet use and problematic online gaming are not the same: Findings from a large nationally representative adolescent sample. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking, 17, 749 - 754. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0475

Kokkinos, C. M., & Antoniadou, N. (2019). Cyberbullying and cybervictimization among undergraduate student teachers through the lens of the general aggression model. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 59 - 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.007

Kopecký, K., Szotkowski, R., & Krejčí, V. (2015). Rizikové formy chování českých a slovenských dětí v prostředí internetu. Olomouc: Univerizta Palackeho. https://doi.org/10.5507/pdf.15.24448619

Lai, F. T. T., & Kwan, J. L. Y. (2017). The presence of heavy Internet using peers is protective of the risk of problematic Internet use (PIU) in adolescents when the amount of use increases. Children & Youth Services Review, 73, 74 - 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.004

Makaruk, K., & Wójcik, S. (2012). Badanie nadużywania Internetu przez młodzież w Polsce. EDU NET ABD. Warszawa: Fundacja Dzieci Niczyje.

McQuail, D. (1984). With the benefit of hindsight: Reflections on uses and gratifications research. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 1, 177 - 193. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295038409360028

Morioka, H., Itani, O., Osaki, Y., Higuchi, S., Jike, M., Kaneita, Y., … Ohida, T. (2016). Association between smoking and problematic Internet use among Japanese adolescents: Large-scale nationwide epidemiological study. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking, 19, 557 - 561. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0182

Mróz, A., & Solecki, R. (2017). Postawy rodziców wobec aktywności nastolatków w internecie w percepcji uczniów (Attitudes of parents toward online activity of teenagers in perception of students). E-mentor, 4, 19 - 24.

Naczelna Izba Kontroli [Supreme Audit Office]. (2016). Przeciwdziałanie e-uzależnieniu dzieci i młodzieży. Kielce: Delegatura Najwyższej Izby Kontroli.

Naukowa i Akademicka Sieć Komputerowa [Scientific and Academic Computer Network]. (2016). Natolatki 3.0. Warszawa: Naukowa i Akademicka Sieć Komputerowa.

Novković Cvetković, B., Stošić, L., & Belousova, A. (2018). Media and information literacy - the basic for application of digital technologies in teaching from the discourses of educational needs of teachers/Medijska i informacijska pismenost - osnova za primjenu digitalnih tehnologija u nastavi iz diskursa obra. Croatian Journal of Education - Hrvatski Časopis Za Odgoj i Obrazovanje, 20, 1089 – 1114. https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v20i4.3001

Ogonowska, A. (2014). Uzależnienia medialne. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Edukacyjne.

Oleszkowicz, A., & Senejko, A. (2013). Psychologia dorastania. Zmiany rozwojowe w dobie globalizacji. Warszawa: PWN.

Olszewska, E. (2013). Uzależnienie od telefonu komórkowego jako nowe wyzwanie edukacji dla bezpieczeństwa. Journal of Science of the Gen. Tadeusz Kosciuszko Military Academy of Land Forces, 170, 16 - 27. doi:10.5604/17318157.1115170

Pace, U., Zappulla, C., Guzzo, G., Di Maggio, R., Laudani, C., & Cacioppo, M. (2014). Internet addiction, temperament, sand the moderator role of family emotional involvement. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12, 52 - 63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-013-9468-8

Pawłowska, B., & Masiak, J. (2014). A comparison of severity of symptoms of Internet addiction in students from Poland, Taiwan and the USA. Current Problems of Psychiatry, 15, 10 - 13.

Pellerone, M., Ramaci, T., & Miccichè, S. (2019). Family functioning, perception of risky behaviour and internet addiction in Italian adolescents. Paper presented at 7th icCSBs 2018 The Annual International Conference on Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences. https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.02.9

Plichta, P., & Pyżalski, J. (2016). Narażenie uczniów ze specjalnymi potrzebami edukacyjnymi na hazard tradycyjny i internetowy oraz inne zachowania ryzykowne. Niepełnosprawność. Dyskursy pedagogiki specjalnej, 24, 222 – 242. https://doi.org/10.4467/25439561.np.16.015.6841

Poprawa, R. (2009). Oczekiwania efektów korzystania z Internetu a problematyczne jego używanie. Psychologia Jakości Życia, 1, 21 - 44.

Poprawa, R. (2012). Problematyczne używanie Internetu-symptomy i metoda diagnozy. Badania wśród dorastającej młodzieży. Psychology of Quality of Life, 1, 57 - 82.

Potyrała, K. (2017). iEdukacja. Synergia nowych mediów i dydaktyki. Ewolucja - antynomie - konteksty. Kraków: Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny. https://doi.org/10.24917/9788380840522

Przepiórka, A., & Błachnio, A. (2013). A Closer Look at Emotions. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 44, 127 - 129. https://doi.org/10.2478/ppb-2013-0014

Przepiorka, A., & Blachnio, A. (2016). Time perspective in Internet and Facebook addiction. Computers in Human Behaviour, 60, 13 - 18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.045

Pyżalski, J. (2016). Od paradygmatu ryzyka do paradygmatu szans–prospołeczne i prorozwojowe używanie internetu przez dzieci i młodzież. In M. Tanaś (ed.), Nastolatki wobec internetu (pp. 55 - 62). Warszawa: NASK.

Pyżalski, J. (2017). Jasna strona-partycypacja i zaangażowanie dzieci i młodzieży w korzystne rozwojowo i prospołeczne działania. Dziecko krzywdzone. Teoria, badania, praktyka, 16, 288 - 303.

Pyżalski, J., Zdrodowska, A., Tomczyk, Ł., & Abramczuk, K. (2019). Polskie badanie EU Kids Online 2018. Najważniejsze wyniki i wnioski. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

Rębisz, S., Sikora, I., & Smoleń-Rębisz, K. (2016). Poczucie samotności a poziom uzależnienia od internetu wśród adolescentów. Edukacja – Technika – Informatyka, 15, 90 - 98. https://doi.org/10.15584/eti.2016.1.13

Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2017). Technological addictions and social connectedness: predictor effect of Internet addiction, social media addiction, digital game addiction and smartphone addiction on social connectedness. Dusunen Adam: Journal of Psychiatry & Neurological Sciences, 30, 202 - 216. https://doi.org/10.5350/DAJPN2017300304

Siuda, P., Stunża, G. D., Dąbrowska, A. J., Klimowicz, M., Kulczycki, E., Piotrowska, R., Rozkosz, E., Sieńko, M., Stachura, K. (2013). Dzieci Sieci 2.0: Kompetencje Komunikacyjne Młodych. Gdańsk: Instytut Kultury Miejskiej.

Spada, M. M., Caselli, G., Slaifer, M., Nikčević, A. V., & Sassaroli, S. (2014). Desire Thinking as a Predictor of Problematic Internet Use. Social Science Computer Review, 32, 474 - 483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313511318

Strittmatter, E., Parzer, P., Brunner, R., Fischer, G., Durkee, T., Carli, V., ... Kaess, M. (2016). A 2-year longitudinal study of prospective predictors of pathological Internet use in adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 725 - 734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0779-0

Tomczyk, Ł., & Selmanagic-Lizde, E. (2018). Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) among youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina - Scale and selected mechanisms. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 541 - 549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.048

Tomczyk, Ł., Srokowski, Ł., & Wąsiński, A. (2016). Kompetencje w zakresie bezpieczeństwa cyfrowego w polskiej szkole. Tarnów: Stowarzyszenie Miasta w Internecie.

Tomczyk, Ł., & Wąsiński, A. (2017). Parents in the process of educational impact in the area of the use of new media by children and teenagers in the family environment. Eğitim ve Bilim, 42, 305 - 323. https://doi.org/10.15390/eb.2017.4674

Vadher, S. B., Panchal, B. N., Vala, A. U., Ratnani, I. J., Vasava, K. J., Desai, R. S., & Shah, A. H. (2019). Predictors of problematic Internet use in school going adolescents of Bhavnagar, India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65, 151 - 157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019827985

Walotek-Ściańska, K. (2017). Persuasion strategies in Polish advertisements addressed to young people. Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Humanitas Zarządzanie, 1, 131 - 146. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.2886

Xiao, J., Li, D., Jia, J., Wang, Y., Sun, W., & Li, D. (2019). The role of stressful life events and the Big Five personality traits in adolescent trajectories of problematic Internet use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours: Journal of The Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviours, 33, 360 - 370. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000466

Young, K. (2009). Understanding online gaming addiction and treatment issues for adolescents. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 37, 355 - 372. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180902942191

Young, K. (2016). Internet Addiction Test. Wheat Lane, Wood Dale: Stoelting.

Young, K., & Clausing, P. (2009). Uwolnić się z Sieci. Katowice: Wydawnictwo św. Jacka.

Zhai, B., Li, D., Jia, J., Liu, Y., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2019). Peer victimization and problematic internet use in adolescents: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of family functioning. Addictive Behaviours, 96, 43 - 49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.016

Ziemba, E. (2016). Factors Affecting the Adoption and Usage of ICTs within Polish Households. Proceedings of the 2016 InSITE Conference. https://doi.org/10.28945/3508